Hyperinflation

- Certain figures in this article use scientific notation for readability.

In economics, hyperinflation is inflation that is very high or out of control. While the real values of the specific economic items generally stay the same in terms of relatively stable foreign currencies, in hyperinflationary conditions the general price level within a specific economy increases rapidly as the functional or internal currency, as opposed to a foreign currency, loses its real value very quickly, normally at an accelerating rate.[1] Definitions used vary from one provided by the International Accounting Standards Board, which describes it as "a cumulative inflation rate over three years approaching 100% (26% per annum compounded for three years in a row)", to Cagan's (1956) "inflation exceeding 50% a month." [2] As a rule of thumb, normal monthly and annual low inflation and deflation are reported per month, while under hyperinflation the general price level could rise by 5 or 10% or even much more every day.

A vicious circle is created in which more and more inflation is created with each iteration of the ever increasing money printing cycle.

Hyperinflation becomes visible when there is an unchecked increase in the money supply (see hyperinflation in Zimbabwe) usually accompanied by a widespread unwillingness on the part of the local population to hold the hyperinflationary money for more than the time needed to trade it for something non-monetary to avoid further loss of real value. Hyperinflation is often associated with wars or their aftermath, currency meltdowns, political or social upheavals, or aggressive bidding on currency exchanges.

Characteristics

In 1956, Phillip Cagan wrote The Monetary Dynamics of Hyperinflation,[3] generally regarded as the first serious study of hyperinflation and its effects. In it, he defined hyperinflation as a monthly inflation rate of at least 50%. International Accounting Standard 1[4] requires a presentation currency. IAS 21[5] provides for translations of foreign currencies into the presentation currency. IAS 29[6] establishes special accounting rules for use in hyperinflationary environments, and lists four factors which can trigger application of these rules:

- The general population prefers to keep its wealth in non-monetary assets or in a relatively stable foreign currency. Amounts of local currency held are immediately invested to maintain purchasing power.

- The general population regards monetary amounts not in terms of the local currency but in terms of a relatively stable foreign currency. Prices may be quoted in that foreign currency.

- Sales and purchases on credit take place at prices that are increased by an amount that will compensate for the expected loss of purchasing power during the credit period, even if the period is short.

- Interest rates, wages and prices are linked to a price index and the cumulative inflation rate over three years approaches, or exceeds, 100%.

In its its Exposure Draft: Severe Hyperinflation – Proposed Amendment to IFRS 1, the IASB has requested comment on a proposed categorization of an economy subject to severe hyperinflation as one in which the currency has both of the following characteristics: (a) a reliable general price index is not available to all entities with transactions and balances in the currency. (b) exchangeability between the currency and a relatively stable foreign currency does not exist.[7]

Root causes of hyperinflation

By definition, inflation is an increase in the Money Supply without a corresponding increase in real output causing an increase in general price levels.[8] Per Milton Friedman "Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon". Hyperinflation is generally considered to be an increase of over 50% in price levels. This increase is caused by decisions on the part of the central bank to increase the money supply at a high rate leading to a loss in its value. Per basic economic principles, an increase in supply of a good will cause a drop in its value. This loss in value is usually exacerbated by an increase in the velocity of money (how fast it is spent) as people rush to exchange (or spend) it for almost anything else. In extreme cases this can cause a complete loss of confidence in the money, similar to a bank run. This loss of confidence causes a rapid increase in the velocity of spending, as people rush to get rid of what they perceive to be a rapidly devaluing asset in exchange for almost anything else of value, causing a corresponding rapid increase in prices. For example, once inflation has become established, sellers try to hedge against it by increasing prices. This leads to further waves of price increases.[9] Hyperinflation will continue as long as the entity responsible for increasing bank credit and/or printing currency continues to engage in excessive money creation. In severe cases, legal tender laws and price controls to prevent discounting the value of paper money relative to hard currency or commodities can fail to force acceptance of the rapidly increasing money supply which lacks intrinsic value, in which case hyperinflation usually continues until the currency is abandoned entirely.[10]

Hyperinflation is generally associated with paper money, which can easily be used to increase the money supply: add more zeros to the plates and print, or even stamp old notes with new numbers.[11] Historically, there have been numerous episodes of hyperinflation in various countries followed by a return to "hard money". Older economies would revert to hard currency and barter when the circulating medium became excessively devalued, generally following a "run" on the store of value.

Hyperinflation effectively wipes out the purchasing power of private and public savings, distorts the economy in favor of extreme consumption and hoarding of real assets, causes the monetary base, whether specie or hard currency, to flee the country, and makes the afflicted area anathema to investment. Hyperinflation is met with drastic remedies, such as imposing the shock therapy of slashing government expenditures or altering the currency basis. One form this may take is dollarization, the use of a foreign currency (not necessarily the U.S. dollar) as a national unit of currency. An example was dollarization in Ecuador, initiated in September 2000 in response to a 75% loss of value of the Ecuadorian sucre in early 2000.

The aftermath of hyperinflation is equally complex. As hyperinflation has always been a traumatic experience for the area which suffers it, the next policy regime almost always enacts policies to prevent its recurrence. Often this means making the central bank very aggressive about maintaining price stability, as was the case with the German Bundesbank or moving to some hard basis of currency such as a currency board. Many governments have enacted extremely stiff wage and price controls in the wake of hyperinflation but this does not prevent further inflating of the money supply by its central bank, and always leads to widespread shortages of consumer goods if the controls are rigidly enforced.

As it allows a government to devalue their spending and displace (or avoid) a tax increase, governments have sometimes resorted to excessively loose monetary policy to meet their expenses. Inflation is effectively a regressive consumption tax,[12] but less overt than levied taxes and therefore harder to understand by ordinary citizens. Inflation can obscure quantitative assessments of the true cost of living, as published price indices only look at data in retrospect, so may increase only months or years later. Monetary inflation can become hyperinflation if monetary authorities fail to fund increasing government expenses from taxes, government debt, cost cutting, or by other means, because either

- during the time between recording or levying taxable transactions and collecting the taxes due, the value of the taxes collected falls in real value to a small fraction of the original taxes receivable; or

- government debt issues fail to find buyers except at very deep discounts; or

- a combination of the above.

Theories of hyperinflation generally look for a relationship between seigniorage and the inflation tax. In both Cagan's model and the neo-classical models, a tipping point occurs when the increase in money supply or the drop in the monetary base makes it impossible for a government to improve its financial position. Thus when fiat money is printed, government obligations that are not denominated in money increase in cost by more than the value of the money created.

From this, it might be wondered why any rational government would engage in actions that cause or continue hyperinflation. One reason for such actions is that often the alternative to hyperinflation is either depression or military defeat. The root cause is a matter of more dispute. In both classical economics and monetarism, it is always the result of the monetary authority irresponsibly borrowing money to pay all its expenses. These models focus on the unrestrained seigniorage of the monetary authority, and the gains from the inflation tax. In Neoliberalism, hyperinflation is considered to be the result of a crisis of confidence. The monetary base of the country flees, producing widespread fear that individuals will not be able to convert local currency to some more transportable form, such as gold or an internationally recognized hard currency. This is a quantity theory of hyperinflation.

In neo-classical economic theory, hyperinflation is rooted in a deterioration of the monetary base, that is the confidence that there is a store of value which the currency will be able to command later. In this model, the perceived risk of holding currency rises dramatically, and sellers demand increasingly high premiums to accept the currency. This in turn leads to a greater fear that the currency will collapse, causing even higher premiums. One example of this is during periods of warfare, civil war, or intense internal conflict of other kinds: governments need to do whatever is necessary to continue fighting, since the alternative is defeat. Expenses cannot be cut significantly since the main outlay is armaments. Further, a civil war may make it difficult to raise taxes or to collect existing taxes. While in peacetime the deficit is financed by selling bonds, during a war it is typically difficult and expensive to borrow, especially if the war is going poorly for the government in question. The banking authorities, whether central or not, "monetize" the deficit, printing money to pay for the government's efforts to survive. The hyperinflation under the Chinese Nationalists from 1939 to 1945 is a classic example of a government printing money to pay civil war costs. By the end, currency was flown in over the Himalayas, and then old currency was flown out to be destroyed.

Hyperinflation is regarded as a complex phenomenon and one explanation may not be applicable to all cases. However, in both of these models, whether loss of confidence comes first, or central bank seigniorage, the other phase is ignited. In the case of rapid expansion of the money supply, prices rise rapidly in response to the increased supply of money relative to the supply of goods and services, and in the case of loss of confidence, the monetary authority responds to the risk premiums it has to pay by "running the printing presses."

Nevertheless the immense acceleration process that occurs during hyperinflation (such as during the German hyperinflation of 1922/23) still remains unclear and unpredictable. The transformation of an inflationary development into the hyperinflation has to be identified as a very complex phenomenon, which could be a further advanced research avenue of the complexity economics in conjunction with research areas like mass hysteria, bandwagon effect, social brain and mirror neurons.[13]

Less commonly, inflation may occur when there is debasement of the coinage: wherein are consistently shaved of some of their silver and gold, increasing the circulating medium and reducing the value of the currency. The "shaved" specie is then often restruck into coins with lower weight of gold or silver. Historical examples include Ancient Rome, China during the Song Dynasty, and the US beginning in 1933. When "token" coins begin circulating, it is possible for the minting authority to engage in fiat creation of currency.

Much attention on hyperinflation naturally centres on the effect on savers whose investment become worthless. Academic economists seem not to have devoted much study on the (positive) effect on debtors. This may be due to the widespread perception that consistently saving a portion of one's income in monetary investments such as bonds or interest-bearing accounts is almost always a wise policy, and usually beneficial to the society of the savers. By contrast, incurring large or long-term debts (though sometimes unavoidable) is viewed as often resulting from irresponsibility or self-indulgence. Interest rate changes often cannot keep up with hyperinflation or even high inflation, certainly with contractually fixed interest rates. (For example, in the 1970s in the United Kingdom inflation reached 25% per annum, yet interest rates did not rise above 15% – and then only briefly – and many fixed interest rate loans existed). Contractually there is often no bar to a debtor clearing his long term debt with "hyperinflated-cash" nor could a lender simply somehow suspend the loan. "Early redemption penalties" were (and still are) often based on a penalty of x months of interest/payment; again no real bar to paying off what had been a large loan. In interwar Germany, for example, much private and corporate debt was effectively wiped out; certainly for those holding fixed interest rate loans.

Models of hyperinflation

Since hyperinflation is visible as a monetary effect, models of hyperinflation center on the demand for money. Economists see both a rapid increase in the money supply and an increase in the velocity of money if the (monetary) inflating is not stopped. Either one, or both of these together are the root causes of inflation and hyperinflation. A dramatic increase in the velocity of money as the cause of hyperinflation is central to the "crisis of confidence" model of hyperinflation, where the risk premium that sellers demand for the paper currency over the nominal value grows rapidly. The second theory is that there is first a radical increase in the amount of circulating medium, which can be called the "monetary model" of hyperinflation. In either model, the second effect then follows from the first — either too little confidence forcing an increase in the money supply, or too much money destroying confidence.

In the confidence model, some event, or series of events, such as defeats in battle, or a run on stocks of the specie which back a currency, removes the belief that the authority issuing the money will remain solvent — whether a bank or a government. Because people do not want to hold notes which may become valueless, they want to spend them. Sellers, realizing that there is a higher risk for the currency, demand a greater and greater premium over the original value. Under this model, the method of ending hyperinflation is to change the backing of the currency, often by issuing a completely new one. War is one commonly cited cause of crisis of confidence, particularly losing in a war, as occurred during Napoleonic Vienna, and capital flight, sometimes because of "contagion" is another. In this view, the increase in the circulating medium is the result of the government attempting to buy time without coming to terms with the root cause of the lack of confidence itself.

In the monetary model, hyperinflation is a positive feedback cycle of rapid monetary expansion. It has the same cause as all other inflation: money-issuing bodies, central or otherwise, produce currency to pay spiralling costs, often from lax fiscal policy, or the mounting costs of warfare. When businesspeople perceive that the issuer is committed to a policy of rapid currency expansion, they mark up prices to cover the expected decay in the currency's value. The issuer must then accelerate its expansion to cover these prices, which pushes the currency value down even faster than before. According to this model the issuer cannot "win" and the only solution is to abruptly stop expanding the currency. Unfortunately, the end of expansion can cause a severe financial shock to those using the currency as expectations are suddenly adjusted. This policy, combined with reductions of pensions, wages, and government outlays, formed part of the Washington consensus of the 1990s.

Whatever the cause, hyperinflation involves both the supply and velocity of money. Which comes first is a matter of debate, and there may be no universal story that applies to all cases. But once the hyperinflation is established, the pattern of increasing the money stock, by whichever agencies are allowed to do so, is universal. Because this practice increases the supply of currency without any matching increase in demand for it, the price of the currency, that is the exchange rate, naturally falls relative to other currencies. Inflation becomes hyperinflation when the increase in money supply turns specific areas of pricing power into a general frenzy of spending quickly before money becomes worthless. The purchasing power of the currency drops so rapidly that holding cash for even a day is an unacceptable loss of purchasing power. As a result, no one holds currency, which increases the velocity of money, and worsens the crisis.

That is, rapidly rising prices undermine money's role as a store of value, so that people try to spend it on real goods or services as quickly as possible. Thus, the monetary model predicts that the velocity of money will rise endogenously as a result of the excessive increase in the money supply. At the point when ordinary purchases are affected by inflation pressures, hyperinflation is out of control, in the sense that ordinary policy mechanisms, such as increasing reserve requirements, raising interest rates or cutting government spending will all be responded to by shifting away from the rapidly dwindling currency and towards other means of exchange.

During a period of hyperinflation, bank runs, loans for 24-hour periods, switching to alternate currencies, the return to use of gold or silver or even barter become common. Many of the people who hoard gold today expect hyperinflation, and are hedging against it by holding specie. There may also be extensive capital flight or flight to a "hard" currency such as the US dollar. This is sometimes met with capital controls, an idea which has swung from standard, to anathema, and back into semi-respectability. All of this constitutes an economy which is operating in an "abnormal" way, which may lead to decreases in real production. If so, that intensifies the hyperinflation, since it means that the amount of goods in "too much money chasing too few goods" formulation is also reduced. This is also part of the vicious circle of hyperinflation.

Once the vicious circle of hyperinflation has been ignited, dramatic policy means are almost always required, simply raising interest rates is insufficient. Bolivia, for example, underwent a period of hyperinflation in 1985, where prices increased 12,000% in the space of less than a year. The government raised the price of gasoline, which it had been selling at a huge loss to quiet popular discontent, and the hyperinflation came to a halt almost immediately, since it was able to bring in hard currency by selling its oil abroad. The crisis of confidence ended, and people returned deposits to banks. The German hyperinflation (1919-Nov. 1923) was ended by producing a currency based on assets loaned against by banks, called the Rentenmark. Hyperinflation often ends when a civil conflict ends with one side winning. Although wage and price controls are sometimes used to control or prevent inflation, no episode of hyperinflation has been ended by the use of price controls alone. However, wage and price controls have sometimes been part of the mix of policies used to halt hyperinflation.

Hyperinflation and the currency

As noted, in countries experiencing hyperinflation, the central bank often prints money in larger and larger denominations as the smaller denomination notes become worthless. This can result in the production of some interesting banknotes, including those denominated in amounts of 1,000,000,000 or more.

- By late 1923, the Weimar Republic of Germany was issuing two-trillion Mark banknotes and postage stamps with a face value of fifty billion Mark. The highest value banknote issued by the Weimar government's Reichsbank had a face value of 100 trillion Mark (100,000,000,000,000; 100 million million).[14][15] At the height of the inflation, one US dollar was worth 4 trillion German marks. One of the firms printing these notes submitted an invoice for the work to the Reichsbank for 32,776,899,763,734,490,417.05 (3.28 × 1019, or 33 quintillion) Marks.[16]

- The largest denomination banknote ever officially issued for circulation was in 1946 by the Hungarian National Bank for the amount of 100 quintillion pengő (100,000,000,000,000,000,000, or 1020; 100 million million million) image. (There was even a banknote worth 10 times more, i.e. 1021 pengő, printed, but not issued image.) The banknotes however did not depict the numbers, "hundred million b.-pengő" ("hundred million trillion pengő") and "one milliard b.-pengő" were spelled out instead. This makes the 100,000,000,000,000 Zimbabwean dollar banknotes the note with the greatest number of zeros shown.

- The Post-World War II hyperinflation of Hungary held the record for the most extreme monthly inflation rate ever — 41,900,000,000,000,000% (4.19 × 1016% or 41.9 quadrillion percent) for July, 1946, amounting to prices doubling every 15.3 hours. By comparison, recent figures (as of 14 November 2008) estimate Zimbabwe's annual inflation rate at 89.7 sextillion (1021) percent.,[17] which corresponds to a monthly rate of 5473%, and a doubling time of about five days. In figures, that is 89,700,000,000,000,000,000,000%.

One way to avoid the use of large numbers is by declaring a new unit of currency (an example being, instead of 10,000,000,000 Dollars, a bank might set 1 new dollar = 1,000,000,000 old dollars, so the new note would read "10 new dollars.") An example of this would be Turkey's revaluation of the Lira on 1 January 2005, when the old Turkish lira (TRL) was converted to the New Turkish lira (TRY) at a rate of 1,000,000 old to 1 new Turkish Lira. While this does not lessen the actual value of a currency, it is called redenomination or revaluation and also happens over time in countries with standard inflation levels. During hyperinflation, currency inflation happens so quickly that bills reach large numbers before revaluation.

Some banknotes were stamped to indicate changes of denomination. This is because it would take too long to print new notes. By the time new notes were printed, they would be obsolete (that is, they would be of too low a denomination to be useful).

Metallic coins were rapid casualties of hyperinflation, as the scrap value of metal enormously exceeded the face value. Massive amounts of coinage were melted down, usually illicitly, and exported for hard currency.

Governments will often try to disguise the true rate of inflation through a variety of techniques. None of these actions addresses the root causes of inflation and they, if discovered, tend to further undermine trust in the currency, causing further increases in inflation. Price controls will generally result in shortages and hoarding and extremely high demand for the controlled goods, resulting in disruptions of supply chains. Products available to consumers may diminish or disappear as businesses no longer find it sufficiently profitable (or may be operating at a loss) to continue producing and/or distributing such goods at the legal prices, further exacerbating the shortages.

Examples of hyperinflation

Angola

Angola experienced hyperinflation from 1991 to 1995. It was a result of exchange restrictions following the introduction of the novo kwanza (AON) to replace the original kwanza (AOK) in 1990. At the first months of 1991, the highest denomination was 50 000 AON. By 1994, the highest denomination was 500 000 kwanzas. In the 1995 currency reform, the readjusted kwanza (AOR) replaced the novo kwanza at the ratio of 1 000 AON to 1 AOR, but hyperinflation continued as further denominations of up to 5 000 000 AOR were issued. In the 1999 currency reform, the kwanza (AOA) was reintroduced at the ratio of 1 million AOR to 1 AOA. Currently, the highest denomination banknote is 2 000 AOA and the overall impact of hyperinflation was 1 AOA = 1 billion AOK.

Argentina

Argentina went through steady inflation from 1975 to 1991. At the beginning of 1975, the highest denomination was 1,000 pesos. In late 1976, the highest denomination was 5,000 pesos. In early 1979, the highest denomination was 10,000 pesos. By the end of 1981, the highest denomination was 1,000,000 pesos. In the 1983 currency reform, 1 peso argentino was exchanged for 10,000 pesos. In the 1985 currency reform, 1 austral was exchanged for 1,000 pesos argentinos. In the 1992 currency reform, 1 new peso was exchanged for 10,000 australes. The overall impact of hyperinflation: 1 (1992) peso = 100,000,000,000 pre-1983 pesos.

Criticism of the official view

Ellen Brown, author of Web of Debt, admits that the left-oriented policy that Argentina had had since 1947, when Juan Peron came to power, did actually create inflation. But the inflation did not become a national crisis until during the eight years that followed Peron's death in 1974. During these years the inflation rose to 206 percent, due to a "deliberate radical devaluation of the currency of the new government, along with a 175 percent increase in oil prices". This devaluation was, as she sees it, done with the hidden purpose of destabilizing the economy (to create a chaos). And it was, in any case, not caused by a sudden and massive increase in the printing of money by the government. She also cites Professor Escudé who writes that this devaluation led both to "the astronomical high inflation" and "to the spread of a speculative financial system that became a hallmark of Argentina's financial life".

Austria

In 1922, inflation in Austria reached 1426%, and from 1914 to January 1923, the consumer price index rose by a factor of 11836, with the highest banknote in denominations of 500,000 krones.[18]

Belarus

Belarus experienced steady inflation from 1994 to 2002. In 1993, the highest denomination was 5,000 rublei. By 1999, it was 5,000,000 rublei. In the 2000 currency reform, the ruble was replaced by the new ruble at an exchange rate of 1 new ruble = 1,000 old rublei. The highest denomination in 2008 was 100,000 rublei, equal to 100,000,000 pre-2000 rublei.

Bolivia

Bolivia experienced its worst inflation between 1984 and 1986. Before 1984, the highest denomination was 1,000 pesos bolivianos. By 1985, the highest denomination was 10 Million pesos bolivianos. In 1985, a Bolivian note for 1 million pesos was worth 55 cents in US dollars, one-thousandth of its exchange value of $5,000 less than three years previously.[19] In the 1987 currency reform, the Peso Boliviano was replaced by the Boliviano at a rate of 1,000,000 : 1.

Bosnia and Herzegovina

Bosnia and Herzegovina went through its worst inflation in 1993. In 1992, the highest denomination was 1,000 dinara. By 1993, the highest denomination was 100,000,000 dinara. In the Republika Srpska, the highest denomination was 10,000 dinara in 1992 and 10,000,000,000 dinara in 1993. 50,000,000,000 dinara notes were also printed in 1993 but never issued.

Brazil

From 1967–1994, the base currency unit was shifted seven times to adjust for inflation in the final years of the Brazilian military dictatorship era. A 1967 cruzeiro was, in 1994, worth less than one trillionth of a US cent, after adjusting for multiple devaluations and note changes. In that same year, inflation reached a record 2,075.8%. A new currency called real was adopted in 1994, and hyperinflation was eventually brought under control.[20] The real was also the currency in use until 1942; 1 (current) real is the equivalent of 2,750,000,000,000,000,000 of Brazil's first currency (called réis in Portuguese).

Bulgaria

In 1996, the Bulgarian economy collapsed due to the slow and mismanaged economic reforms of several governments in a row, shortages of wheat, and an unstable and decentralized banking system, which led to an inflation rate of 311% and the collapse of the lev, with the exchange rate to dollars reaching 3000. When pro-reform forces came into power in the spring 1997, an ambitious economic reform package, including introduction of a currency board regime and pegging the Bulgarian Lev to the German Deutsche Mark (and consequently to the euro), was agreed to with the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, and the economy began to stabilize.

China

As the first user of fiat currency, China has had an early history of troubles caused by hyperinflation. The Yuan Dynasty printed huge amounts of fiat paper money to fund their wars, and the resulting hyperinflation, coupled with other factors, led to its demise at the hands of a revolution. The Republic of China went through the worst inflation 1948–49. In 1947, the highest denomination was 50,000 yuan. By mid-1948, the highest denomination was 180,000,000 yuan. The 1948 currency reform replaced the yuan by the gold yuan at an exchange rate of 1 gold yuan = 3,000,000 yuan. In less than a year, the highest denomination was 10,000,000 gold yuan. In the final days of the civil war, the Silver Yuan was briefly introduced at the rate of 500,000,000 Gold Yuan. Meanwhile the highest denomination issued by a regional bank was 6,000,000,000 yuan (issued by Xinjiang Provincial Bank in 1949). After the renminbi was instituted by the new communist government, hyperinflation ceased with a revaluation of 1:10,000 old Renminbi in 1955. The overall impact of inflation was 1 Renminbi = 15,000,000,000,000,000,000 pre-1948 yuan.

France

During the French Revolution, the National Assembly issued bonds backed by seized church property called Assignats. These evolved into fiat legal tender money, were overprinted and caused hyperinflation. Napoleon replaced them with the franc in 1803, at which time the assignats were basically worthless.

Free City of Danzig

Danzig went through its worst inflation in 1923. In 1922, the highest denomination was 1,000 Mark. By 1923, the highest denomination was 10,000,000,000 Mark.

Georgia

Georgia went through its worst inflation in 1994. In 1993, the highest denomination was 100,000 coupons [kuponi]. By 1994, the highest denomination was 1,000,000 coupons. In the 1995 currency reform, a new currency, the lari, was introduced with 1 lari exchanged for 1,000,000 coupons.

Germany

Germany went through its worst inflation in 1923. In 1922, the highest denomination was 50,000 Mark. By 1923, the highest denomination was 100,000,000,000,000 Mark. In December 1923 the exchange rate was 4,200,000,000,000 Marks to 1 US dollar.[21] In 1923, the rate of inflation hit 3.25 × 106 percent per month (prices double every two days). Beginning on 20 November 1923, 1,000,000,000,000 old Marks were exchanged for 1 Rentenmark so that 4.2 Rentenmarks were worth 1 US dollar, exactly the same rate the Mark had in 1914.[21]

Greece

Greece went through its worst inflation in 1944. In 1942, the highest denomination was 50,000 drachmai. By 1944, the highest denomination was 100,000,000,000 drachmai. In the 1944 currency reform, 1 new drachma was exchanged for 50,000,000,000 drachmai. Another currency reform in 1953 replaced the drachma at an exchange rate of 1 new drachma = 1,000 old drachmai. The overall impact of hyperinflation: 1 (1953) drachma = 50,000,000,000,000 pre 1944 drachmai. The Greek monthly inflation rate reached 8.5 billion percent in October 1944.

Hungary, 1922–24

The Treaty of Trianon and political instability between 1919 and 1924 led to a major inflation of Hungary’s currency. Unable to tax adequately, the government resorted to printing money and by 1922 inflation in Hungary had reached 98% per month.

Hungary, 1945–46

Hungary went through the worst inflation ever recorded between the end of 1945 and July 1946. In 1944, the highest denomination was 1,000 pengő. By the end of 1945, it was 10,000,000 pengő. The highest denomination in mid-1946 was 100,000,000,000,000,000,000 pengő. A special currency the adópengő – or tax pengő – was created for tax and postal payments.[22] The value of the adópengő was adjusted each day, by radio announcement. On 1 January 1946 one adópengő equaled one pengő. By late July, one adópengő equaled 2,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 or 2×1021 pengő. When the pengő was replaced in August 1946 by the forint, the total value of all Hungarian banknotes in circulation amounted to 1/1,000 of one US dollar.[23] It is the most severe known incident of inflation recorded, peaking at 1.3 × 1016 percent per month (prices double every 15 hours).[24] The overall impact of hyperinflation: On 18 August 1946, 400,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 or 4×1029 (four hundred octillion (short scale)) pengő became 1 forint.

Some historians believe[25] that this hyperinflation was purposely started by trained Russian Marxists in order to destroy the Hungarian middle and upper classes.

Israel

Inflation accelerated in the 1970s, rising steadily from 13% in 1971 to 111% in 1979. From 133% in 1980, it leaped to 191% in 1983 and then to 445% in 1984, threatening to become a four-digit figure within a year or two. In 1985 Israel froze most prices by law and enacted other measures as part of an economic stabilization plan. That same year, inflation more than halved, to 185%. Within a few months, the authorities began to lift the price freeze on some items; in other cases it took almost a year. By 1986, inflation was down to 19%.

Krajina

The Republic of Serbian Krajina went through its worst inflation in 1993. In 1992, the highest denomination was 50,000 dinara. By 1993, the highest denomination was 50,000,000,000 dinara. Note that this unrecognized country was reincorporated into Croatia in 1995.

Mexico

In spite of the Oil Crisis of the late 1970s (Mexico is a producer and exporter), and due to excessive social spending, Mexico defaulted on its external debt in 1982. As a result, the country suffered a severe case of capital flight and several years of hyperinflation and peso devaluation. On 1 January 1993, Mexico created a new currency, the nuevo peso ("new peso", or MXN), which chopped 3 zeros off the old peso, an inflation rate of 10,000% over the several years of the crisis. (One new peso was equal to 1000 of the obsolete MXP pesos).

North Korea, 1947–2009

Though the North Korean Won never technically failed, and is still the official currency of the reclusive communist nation, a 2009 revaluation showed the rest of the world rare cracks in the monolithic image Pyongyang presents. The government gave citizens seven days to turn in their old won for new won – with 1,000 of the old worth 10 of the new – but allowed a maximum exchange of 150,000 of the old won. That means each adult can exchange about US$740-worth of won. The revaluation and exchange cap wiped out the savings of many North Koreans, and reportedly caused unrest in parts of the country. According to a September 2009 BBC report, some department stores in Pyongyang even stopped accepting North Korean won, instead insisting upon payment in U.S. Dollars, Chinese Yuan, Euros, or even Japanese Yen.

Nicaragua

Nicaragua went through the worst inflation from 1987 to 1990. From 1943 to April 1971, one US dollar equalled 7 córdobas. From April 1971-early 1978, one US dollar was worth 10 córdobas. In early 1986, the highest denomination was 10,000 córdobas. By 1987, it was 1,000,000 córdobas. In the 1988 currency reform, 1 new córdoba was exchanged for 10,000 old córdobas. The highest denomination in 1990 was 100,000,000 new córdobas. In the 1991 currency reform, 1 new córdoba was exchanged for 5,000,000 old córdobas. The overall impact of hyperinflation: 1 (1991) córdoba = 50,000,000,000 pre-1988 córdobas.

Peru

Peru experienced its worst inflation from 1988–1990. In the 1985 currency reform, 1 inti was exchanged for 1,000 soles. In 1986, the highest denomination was 1,000 intis. But in September 1988, monthly inflation went to 132%. In August 1990, monthly inflation was 397%. The highest denomination was 5,000,000 intis by 1991. In the 1991 currency reform, 1 nuevo sol was exchanged for 1,000,000 intis. The overall impact of hyperinflation: 1 nuevo sol = 1,000,000,000 (old) soles.

Philippines

The Japanese government occupying the Philippines during the World War II issued fiat currencies for general circulation. The Japanese-sponsored Second Philippine Republic government led by Jose P. Laurel at the same time outlawed possession of other currencies, most especially "guerilla money." The fiat money was dubbed "Mickey Mouse Money" because it is similar to play money and is next to worthless. Survivors of the war often tell tales of bringing suitcase or bayong (native bags made of woven coconut or buri leaf strips) overflowing with Japanese-issued bills. In the early times, 75 Mickey Mouse pesos could buy one duck egg.[26] In 1944, a box of matches cost more than 100 Mickey Mouse pesos.[27]

In 1942, the highest denomination available was 10 pesos. Before the end of the war, because of inflation, the Japanese government was forced to issue 100, 500 and 1000 peso notes.

Poland, 1921–1924

After Poland’s independence in 1918, the country soon began experiencing extreme inflation. By 1921, prices had already risen 251 times above those of 1914, but in the following three years they rose by 988,223%[28] with a peak rate in late 1923 of prices doubling every nineteen and a half days.[29] At independence there was 8 marek per US dollar, but by 1923 the exchange rate was 6,375,000 marek (mkp) for 1 US dollar. The highest denomination was 10,000,000 mkp. In the 1924 currency reform there was a new currency introduced: 1 zloty = 1,800,000 mkp.

Poland, 1989–1991

Poland experienced a second hyperinflation between 1989 and 1991. The highest denomination in 1989 was 200,000 zlotych. It was 1,000,000 zlotych in 1991 and 2,000,000 zlotych in 1992; the exchange rate was 9500 zlotych for 1 US dollar in January 1990 and 19600 zlotych at the end of August 1992. In the 1994 currency reform, 1 new zloty was exchanged for 10,000 old zlotych and 1 US$ exchange rate was ca. 2.5 zlotych (new).

Republika Srpska

Republika Srpska was a breakaway region of Bosnia. As with Krajina, it pegged its currency, the Republika Srpska dinar, to that of Yugoslavia. Their bills were almost the same as Krajina's, but they issued fewer and did not issue currency after 1993.

Romania

Romania experienced hyperinflation in the 1990s. The highest denomination in 1990 was 100 lei and in 1998 was 100,000 lei. By 2000 it was 500,000 lei. In early 2005 it was 1,000,000 lei. In July 2005 the leu was replaced by the new leu at 10,000 old lei = 1 new leu. Inflation in 2005 was 9%. [2] In July 2005 the highest denomination became 500 lei (= 5,000,000 old lei).

Soviet Union / Russian Federation

Between 1921 and 1922, inflation in the Soviet Union reached 213%.

In 1992, the first year of post-Soviet economic reform, inflation was 2,520%. In 1993, the annual rate was 840%, and in 1994, 224%. The ruble devalued from about 40 r/$ in 1991 to about 5,000 r/$ in late 1997. In 1998, a denominated ruble was introduced at the exchange rate of 1 new ruble = 1,000 pre-1998 rubles. In the second half of the same year, ruble fell to about 30 r/$ as a result of financial crisis.

Taiwan

As the Chinese Civil War reached its peak, Taiwan also suffered from the hyperinflation that has ravaged China in late 1940s. Highest denomination issued was a 1,000,000 Dollar Bearer's Cheque. Inflation was finally brought under control at introduction of New Taiwan Dollar in 15 June 1949 at rate of 40,000 old Dollar = 1 New Dollar

Ukraine

Ukraine experienced its worst inflation between 1993 and 1995. In 1992, the Ukrainian karbovanets was introduced, which was exchanged with the defunct Soviet ruble at a rate of 1 UAK = 1 SUR. Before 1993, the highest denomination was 1,000 karbovantsiv. By 1995, it was 1,000,000 karbovantsiv. In 1996, during the transition to the Hryvnya and the subsequent phase out of the karbovanets, the exchange rate was 100,000 UAK = 1 UAH. This translates to a hyperinflation rate of approximately 1,400% per month. By some estimates, inflation for the entire calendar year of 1993 was 10,000% or higher, with retail prices reaching over 100 times their pre-1993 level by the end of the year.[30]

United States

During the Revolutionary War, when the Continental Congress authorized the printing of paper currency called continental currency. The monthly inflation rate reached a peak of 47 percent in November 1779 (Bernholz 2003: 48). These notes depreciated rapidly, giving rise to the expression "not worth a continental."

A second close encounter occurred during the U.S. Civil War, between January 1861 and April 1865, the Lerner Commodity Price Index of leading cities in the eastern Confederacy states increased from 100 to over 9,000.[31] As the Civil War dragged on, the Confederate dollar had less and less value, until it was almost worthless by the last few months of the war. Similarly, the Union government inflated its greenbacks, with the monthly rate peaking at 40 percent in March 1864 (Bernholz 2003: 107).[32]

Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia went through a period of hyperinflation and subsequent currency reforms from 1989–1994. The highest denomination in 1988 was 50,000 dinars. By 1989 it was 2,000,000 dinars. In the 1990 currency reform, 1 new dinar was exchanged for 10,000 old dinars. In the 1992 currency reform, 1 new dinar was exchanged for 10 old dinars. The highest denomination in 1992 was 50,000 dinars. By 1993, it was 10,000,000,000 dinars. In the 1993 currency reform, 1 new dinar was exchanged for 1,000,000 old dinars. However, before the year was over, the highest denomination was 500,000,000,000 dinars. In the 1994 currency reform, 1 new dinar was exchanged for 1,000,000,000 old dinars. In another currency reform a month later, 1 novi dinar was exchanged for 13 million dinars (1 novi dinar = 1 German mark at the time of exchange). The overall impact of hyperinflation: 1 novi dinar = 1 × 1027~1.3 × 1027 pre 1990 dinars. Yugoslavia's rate of inflation hit 5 × 1015 percent cumulative inflation over the time period 1 October 1993 and 24 January 1994.

Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo)

Zaire went through a period of inflation between 1989 and 1996. In 1988, the highest denomination was 5,000 zaires. By 1992, it was 5,000,000 zaires. In the 1993 currency reform, 1 nouveau zaire was exchanged for 3,000,000 old zaires. The highest denomination in 1996 was 1,000,000 nouveaux zaires. In 1997, Zaire was renamed the Congo Democratic Republic and changed its currency to francs. 1 franc was exchanged for 100,000 nouveaux zaires. One post-1997 franc was equivalent to 3 × 1011 pre 1989 zaires.

Zimbabwe

Hyperinflation in Zimbabwe was one of the few instances that resulted in the abandonment of the local currency. At independence in 1980, the Zimbabwe dollar (ZWD) was worth about USD 1.25. Afterwards, however, rampant inflation and the collapse of the economy severely devalued the currency. Inflation was steady before Robert Mugabe in 1998 began a program of land reforms that primarily focused on taking land from white farmers and redistributing those properties and assets to black farmers, which sent food production and revenues from export of food plummeting.[33][34][35] The result was that to pay its expenditures Mugabe’s government and Gideon Gono’s Reserve Bank printed more and more notes with higher face values.

Hyperinflation began early in the twenty-first century, reaching 624% in 2004. It fell back to low triple digits before surging to a new high of 1,730% in 2006. The Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe revalued on 1 August 2006 at a ratio of 1 000 ZWD to each second dollar (ZWN), but year-to-year inflation rose by June 2007 to 11,000% (versus an earlier estimate of 9,000%). Larger denominations were progressively issued:

- 5 May: banknotes or "bearer cheques" for the value of ZWN 100 million and ZWN 250 million.[36]

- 15 May: new bearer cheques with a value of ZWN 500 million (then equivalent to about USD 2.50).[37]

- 20 May: a new series of notes (“agro cheques”) in denominations of $5 billion, $25 billion and $50 billion.

- 21 July: “agro cheque” for $100 billion.[38]

Inflation by 16 July officially surged to 2,200,000%[39] with some analysts estimating figures surpassing 9,000,000 percent.[40] As of 22 July 2008 the value of the ZWN fell to approximately 688 billion per 1 USD, or 688 trillion pre-August 2006 Zimbabwean dollars.[41]

| Date of redenomination |

Currency code |

Value |

|---|---|---|

| 1 Aug 2006 | ZWN | 1 000 ZWD |

| 1 Aug 2008 | ZWR | 1010 ZWN = 1013 ZWD |

| 2 Feb 2009 | ZWL | 1012 ZWR = 1022 ZWN = 1025 ZWD |

On 1 August 2008, the Zimbabwe dollar was redenominated at the ratio of 1010 ZWN to each third dollar (ZWR).[42] On 19 August 2008, official figures announced for June estimated the inflation over 11,250,000%.[43] Zimbabwe's annual inflation was 231,000,000% in July[44] (prices doubling every 17.3 days). For periods after July 2008, no official inflation statistics were released. Prof. Steve H. Hanke overcame the problem by estimating inflation rates after July 2008 and publishing the Hanke Hyperinflation Index for Zimbabwe.[45] Prof. Hanke’s HHIZ measure indicated that the inflation peaked at an annual rate of 89.7 sextillion percent (89,700,000,000,000,000,000,000%) in mid-November 2008. The peak monthly rate was 79.6 billion percent, which is equivalent to a 98% daily rate, or around 7× 10108 percent yearly rate. At that rate, prices were doubling every 24.7 hours. Note that many of these figures should be considered mostly theoretic, since the hyperinflation did not proceed at that rate a whole year.[46]

At its November 2008 peak, Zimbabwe's rate of inflation approached, but failed to surpass, Hungary's July 1946 world record.[46] On 2 February 2009, the dollar was redenominated for the fourth time at the ratio of 1012 ZWR to 1 ZWL, only three weeks after the $100 trillion banknote was issued on 16 January,[47][48] but hyperinflation waned by then as official inflation rates in USD were announced and foreign transactions were legalised,[46] and on 12 April the dollar was abandoned in favour of using only foreign currencies. The overall impact of hyperinflation was 1 ZWL = 1025 ZWD.

Worst hyperinflations in world history

| Highest monthly inflation rates in history[46] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Currency name | Month with highest inflation rate | Highest monthly inflation rate | Equivalent daily inflation rate | Time required for prices to double |

| Hungary | Hungarian pengő | July 1946 | 4.19 × 1016 % | 207.19% | 15 hours |

| Zimbabwe | Zimbabwe dollar | November 2008 | 7.96 × 1010 % | 98.01% | 24.7 hours |

| Yugoslavia | Yugoslav dinar | January 1994 | 3.13 × 108 % | 64.63% | 1.4 days |

| Germany | German Papiermark | October 1923 | 29,500% | 20.87% | 3.7 days |

| Greece | Greek drachma | October 1944 | 13,800% | 17.84% | 4.3 days |

| Taiwan (Republic of China) | Old Taiwan dollar | May 1949 | 2,178% | 10.98% | 6.7 days |

Units of inflation

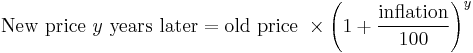

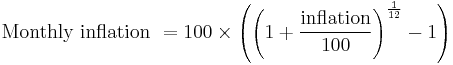

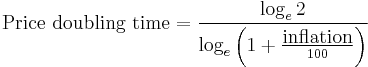

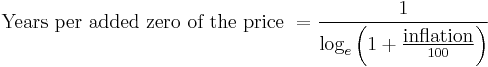

Inflation rate is usually measured in percent per year. It can also be measured in percent per month or in price doubling time.

| Old price | New price 1 year later | New price 10 years later | New price 100 years later | (Annual) inflation [%] | Monthly inflation [%] |

Price doubling time [years] |

Zero add time [years] | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

|

|

0.01 |

|

|

23028 | ||||||||||

| 1 |

|

|

|

0.1 |

|

|

2300 | ||||||||||

| 1 |

|

|

|

0.3 |

|

|

769 | ||||||||||

| 1 |

|

|

|

1 |

|

|

231 | ||||||||||

| 1 |

|

|

|

3 |

|

|

77.9 | ||||||||||

| 1 |

|

|

|

10 |

|

|

24.1 | ||||||||||

| 1 |

|

|

|

100 |

|

|

3.32 | ||||||||||

| 1 |

|

|

|

900 |

|

|

1 | ||||||||||

| 1 |

|

|

|

3000 |

|

|

0.671 (8 months) | ||||||||||

| 1 |

|

|

|

1014 |

|

|

0.0833 (1 month) | ||||||||||

| 1 |

|

|

|

1.67 × 1075 |

|

|

0.0137 (5 days) | ||||||||||

| 1 |

|

|

|

1.05 × 102,639 |

|

|

0.000379 (3.3 hours) |

Often, at redenominations, three zeroes are cut from the bills. It can be read from the table that if the (annual) inflation is for example 100%, it takes 3.32 years to produce one more zero on the price tags, or 3 × 3.32 = 9.96 years to produce three zeroes. Thus can one expect a redenomination to take place about 9.96 years after the currency was introduced.

Computerized transaction issues

Western Europe, North America and many parts of Asia and Australasia have economies that depend heavily on computerized transaction procession of money transfers. However, most nations that are subject to hyperinflation risk have not done assessments as to the ability of the electronic part of the finance system to remain intact under hyperinflation.

It is assumed (based upon IT practices for transnational processing that have evolved since the 1970s) that most money held by banks is not represented by 64 bit floating numbers. Under hyperinflation conditions most bank processing systems could fail due to overflow conditions [3].

See also

- Biflation

- Chronic inflation

- Gold as an investment

- Inflation accounting

- Inflationism

- Deflation

- List of economics topics

- Zero stroke

References

- ^ O'Sullivan, Arthur; Steven M. Sheffrin (2003). Economics: Principles in action. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey 07458: Pearson Prentice Hall. pp. 341, 404. ISBN 0-13-063085-3.

- ^ Ragan, Christopher; Lipsey, Richard (2008). Macroeconomics. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Pearson Education Canada. p. 645. ISBN 0-558-05845-0.

- ^ Phillip Cagan, The Monetary Dynamics of Hyperinflation, in Milton Friedman (Editor), Studies in the Quantity Theory of Money, Chicago: University of Chicago Press (1956).

- ^ "IAS 1 PRESENTATION OF FINANCIAL STATEMENTS". IASB. http://www.iasplus.com/standard/ias01.htm. Retrieved 2008-09-19.

- ^ "IAS 21 THE EFFECTS OF CHANGES IN FOREIGN EXCHANGE RATES". IASB. http://www.iasplus.com/standard/ias21.htm. Retrieved 2008-09-19.

- ^ Deloitte. FINANCIAL REPORTING IN HYPERINFLATIONARY ECONOMIES. Deloitte, IAS Plus. http://www.iasplus.com/standard/ias29.htm.

- ^ Severe Hyperinflation: Proposed amendment to IFRS-1, page 6

- ^ http://inflationdata.com/articles/2008/07/16/inflation-cause-and-effect/

- ^ Hyperinflation: causes, cures, Bernard Mufute

- ^ Hyperinflation: causes, cures Bernard Mufute, 2003-10-02, 'Hyperinflation has its root cause in money growth, which is not supported by growth in the output of goods and services. Usually the excessive money supply growth is caused by financing of the government budget deficit through the printing of money.'

- ^ http://blogs.wsj.com/marketbeat/2008/03/06/jefferson-county-memories/ Jefferson County Miracles, Wall Street Journal, March 6, 2008.

- ^ http://www.ssc.uwo.ca/economics/econref/workingpapers/researchreports/wp2000/wp2000_1.pdf

- ^ Wolfgang Chr. Fischer (Editor), German Hyperinflation 1922/23 – A Law and Economics Approach, Eul Verlag, Köln, Germany 2010, p.124

- ^ 1 billion in the German long scale = 1000 milliard = 1 trillion US scale.

- ^ Values of the most important German Banknotes of the Inflation Period from 1920 – 1923

- ^ The Penniless Billionaires, Max Shapiro, New York Times Book Co., 1980, page 203, ISBN 0-8129-0923-2 Shipiro comments: "Of course, one must not forget the 5 pfennig!"

- ^ Hanke, Steve H. (17 November 2008). "New Hyperinflation Index (HHIZ) Puts Zimbabwe Inflation at 89.7 sextillion percent". The Cato Institute. http://www.cato.org/zimbabwe. Retrieved 17 November 2008.

- ^ http://www.fee.org/pdf/the-freeman/0604RMEbeling.pdf

- ^ Weatherford, Jack (1997). The History of Money. Three Rivers Press. p. 194. ISBN 0609801724.

- ^ How Brazil Beat Hyperinflation, by Leslie Evans

- ^ a b Bresciani-Turroni, page 335

- ^ Hungary: Postal history – Hyperinflation (part 2)

- ^ Judt, Tony (2006). Postwar: A History of Europe Since 1945. Penguin. p. 87. ISBN 0143037757.

- ^ Zimbabwe hyperinflation 'will set world record within six weeks' Zimbabwe Situation 2008-11-14

- ^ Hungary: Postal History – Hyperinflation

- ^ Barbara A. Noe (7 August 2005). "A Return to Wartime Philippines". Los Angeles Times. http://www.latimes.com/news/local/valley/la-tr-philippines7aug07,0,648886,full.story?coll=la-editions-valley. Retrieved 2006-11-16.

- ^ Agoncillo, Teodoro A. & Guerrero, Milagros C., History of the Filipino People, 1986, R.P. Garcia Publishing Company, Quezon City, Philippines

- ^ [1]

- ^ Hyperinflation: Mugabe Versus Milosević

- ^ Yuriy Skolotiany, The past and the future of Ukrainian national currency, Interview with Anatoliy Halchynsky, Mirror Weekly, #33(612), 2—8 September 2006

- ^ Money and Finance in the Confederate States of America, Marc Weidenmier, Claremont McKenna College

- ^ http://www.cato.org/pubs/journal/cj29n2/cj29n2-8.pdf

- ^ Land reform in Zimbabwe

- ^ Zimbabwe famine

- ^ Greenspan, Alan. The Age of Turbulence: Adventures in a New World. New York: The Penguin Press. 2007. Page 339.

- ^ Zimbabwe issues 250 mn dollar banknote to tackle price spiral- International Business-News-The Economic Times

- ^ BBC NEWS: Zimbabwe bank issues $500m note

- ^ http://uk.news.yahoo.com/afp/20080719/tbs-zimbabwe-economy-inflation-5268574.html

- ^ "Zimbabwe inflation at 2,200,000%". BBC News. 16 July 2008. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/business/7509715.stm. Retrieved 26 March 2010.

- ^ http://www.thezimbabweindependent.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=20637:inflation-gallops-ahead&catid=28:zimbabwe%20business%20stories&Itemid=59

- ^ http://www.zimbabweanequities.com/

- ^ Reuters. http://africa.reuters.com/business/news/usnBAN034008.html.

- ^ "Zimbabwe inflation rockets higher". BBC News. 19 August 2008. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/business/7569894.stm. Retrieved 26 March 2010.

- ^ http://news.yahoo.com/s/afp/20081009/wl_africa_afp/zimbabweeconomyinflation

- ^ Steve H. Hanke, "New Hyperinflation Index (HHIZ) Puts Zimbabwe Inflation at 89.7 Sextillion Percent.” Washington, D.C.: Cato Institute. (Retrieved 17 November 2008) (http://www.cato.org/zimbabwe)

- ^ a b c d Steve H. Hanke and Alex K. F. Kwok, "On the Measurement of Zimbabwe’s Hyperinflation." Cato Journal, Vol. 29, No. 2 (Spring/Summer 2009). (http://www.cato.org/pubs/journal/cj29n2/cj29n2-8.pdf)

- ^ http://www.africasia.com/services/news/newsitem.php?area=africa&item=090116063500.qczog3x4.php

- ^ Zimbabwe dollar sheds 12 zeros, BBC News, 2009-02-02, http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/africa/7865259.stm, retrieved 2008-02-02

Further reading

- Costantino Bresciani-Turroni, The Economics of Inflation (English transl.). Northampton, England: Augustus Kelly Publishers, 1937, http://mises.org/books/economicsofinflation.pdf on the German 1919–1923 inflation.

- Shun-Hsin Chou, The Chinese Inflation 1937–1949, New York, Columbia University Press, 1963, Library of Congress Cat. 62-18260.

- Andrew Dickson White, Fiat Money Inflation in France, Caxton Printers, Idaho, 1969. a popular description of the 1789–1799 inflation.

- Steve H. Hanke, “Zimbabwe: From Hyperinflation to Growth.” Development Policy Analysis No. 6. Washington, D.C.: Cato Institute, Center for Global Liberty and Prosperity. (June 25, 2008) (http://www.cato.org/pubs/dpa/dpa6.pdf)

- Steve H. Hanke and Alex K. F. Kwok, "On the Measurement of Zimbabwe’s Hyperinflation." Cato Journal, Vol. 29, No. 2 (Spring/Summer 2009). (http://www.cato.org/pubs/journal/cj29n2/cj29n2-8.pdf)

- Wolfgang Chr. Fischer (Editor), "German Hyperinflation 1922/23 – A Law and Economics Approach", Eul Verlag, Köln, Germany 2010.

External links

Bold text